Same same but different

Comparing the Internet Era with the Rise of GenAI

1.

Every transformative technology gets compared to the internet, and few live up to the comparison. But GenAI's relationship to the internet isn't a simple one of similarity or succession.

If you had engaged with the internet in the nineties, you’d probably see the signs today. Here is a technology so foundational it will impact every sphere of our lives: this was what was said about the internet back then, and it turned out right. What began as a novelty transformed, over the next decade, into something indispensable.

These days, the talk is about GenAI. Columnists and experts weigh in daily with analyses and opinions. There’s the excitement one felt in the early internet years, plenty of hype, and large investments — and there are skeptics too. Unlike last time, though, it’s hard to keep up with the speed of change. But beneath these surface-level themes, the similarities, contrasts, and interplay between the two eras make for a fascinating study.

2.

Much has been written about how we’ve lost the spirit of the internet’s early years. That early internet — a decentralized haven of quirky personal websites, community-driven forums populated by eccentrics and enthusiasts — has given way to a landscape dominated by a handful of platforms that control, through algorithms tuned to capture attention, how we publish, consume, and behave.

GenAI is already worsening this situation. AI-generated summaries on search pages, bot responses in discussion spaces, AI slop on the web: all of this influences what we consume and how. Perhaps more worryingly, AI is also changing how — and how fast — we create content.

A theme linking the two eras is the loss of control experienced by creators and consumers.

First came platforms that set boundaries on how people produced and consumed content, and how people connected with one another. From open, freestyle blogs that linked to one another, we went to closed platforms like Facebook and Twitter that controlled not only the format of content but also whom you could share it with.

What followed was the rise of the algorithm that defined how your feed looked. With RSS, I controlled what I saw and read – social media feeds took away this ability. Algorithms also subtly influenced how we wrote and how we shared. Distribution – using techniques that tried to follow the algorithm’s intent – became part of the author’s toolkit. We used the “right” keywords, we embedded tags, and even placed links in comments to maximize reach.

These days, algorithmic feeds are complemented by AI-generated summaries. Original articles and documents, artifacts you could earlier search for and read in their entirety, are now abstracted in texts generated by a Large Language Model.

For creators, this AI wave is a lot more disruptive. The internet wave mostly influenced content distribution, but this one gets to the center: it alters the act of creation itself. Creators may be conflicted about the questions of originality and ownership this brings up, and how they use AI may vary in degree. But very few will remain unaffected.

3.

The enthusiasm of the internet's early days was shared by a diverse pool of individuals: academics sharing research, hobbyists documenting niche interests, artists experimenting with digital media, small business owners reaching new customers, and activists organizing communities around causes. People from all walks of life set up blogs and embraced the freedom to create and connect without an intermediary.

These days, while millions of users all over the world use ChatGPT, most AI devotees are from the tech and business community: programmers, startup founders, VCs, consultants. Creative folks are also experimenting with AI, but many are concerned, confused, or tentative. White-collar workers, while benefiting from the productivity gains of using AI, are worried about their jobs. We also have the doomers prophesying an apocalypse, a rare tendency during the early internet era.

It’s not about technology alone. The dial’s shift – from enthusiasm for the internet to concern and skepticism towards AI – highlights a cultural swing we’ve seen in the years between these two eras.

The early internet emerged during an era of relative technological innocence. People experienced the web as liberation from traditional gatekeepers —publishers, broadcasters, institutions that controlled information flow. The prevailing narrative was democratization and empowerment, and early adopters had direct evidence supporting this optimism through their own experiences creating and connecting online.

By contrast, GenAI arrives after two decades of documented technological disruption. We've witnessed how platforms consolidated power, how algorithms manipulated behavior, and how social media influenced elections and affected mental health. We've seen how technologies that promised connection often delivered isolation and how systems that promised objectivity often amplified bias.

We are much less naive now about the promise of new technology, and more sensitive to its downstream effects.

Unsurprisingly, some believe that this new technology will solve problems created by the older one. Mental health chatbots are the fastest growing category among GenAI apps. Few see the irony here.

4.

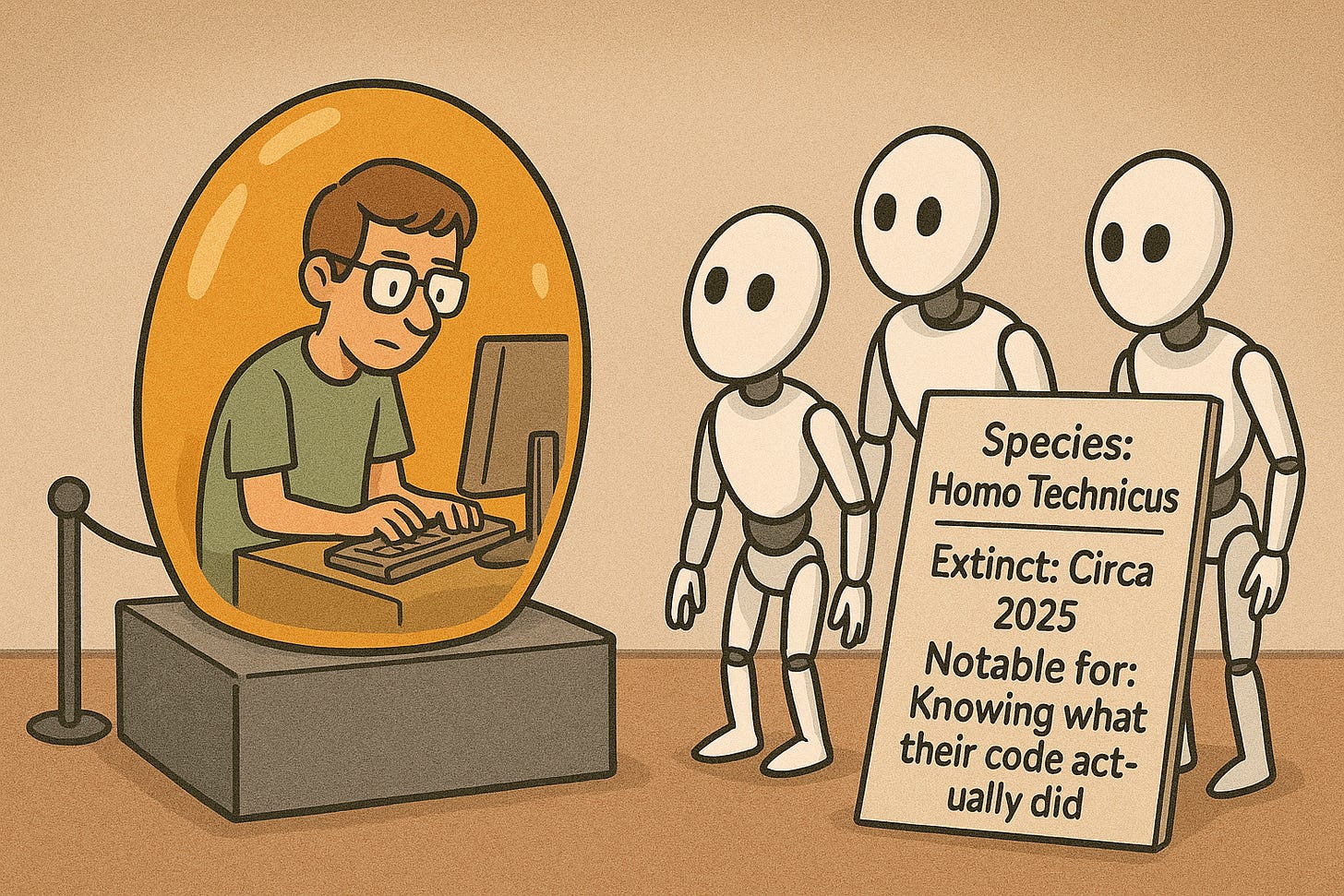

The internet made it much easier to create and distribute content, which led to an explosion of text, photos, and videos. The barrier to content creation has been lowered further with GenAI, but a new category has now emerged: software. Vibe coding allows anyone with imagination to create an app. We’ll soon see a surge of software applications created by people who don’t know how to code.

This is one area where GenAI is fueling enthusiasm and ambition, mirroring what we saw from content creators in the internet era. But the differences between the two have significant implications.

When the early internet democratized content creation, people were essentially gaining access to content creation tools and a distribution network. But the fundamental nature of content creation remained largely unchanged. Writing an essay, taking a photograph, or recording a video still required the same human capabilities it always had. The internet made distribution democratic, but creation itself retained its earlier character.

Software democratization through AI is different. Here, we're not just removing barriers to distribution, but potentially removing barriers to a form of creation that previously required specialized knowledge and significant time investment. When someone uses vibe coding to create an application, they're bypassing years of technical education and practice that traditional programming demands.

Content democratization meant more people could share their existing capabilities with the world. Software democratization might mean people can create things that exceed their existing capabilities—or at least their existing technical knowledge.

There are several reasons why this distinction is important.

Quality is the first one. A bad blog post might waste readers' time, but it cannot crash systems or compromise security. Vibe-coded software, however, can create quality and reliability challenges that dwarf those we experienced with user-generated content. The emerging "anyone can code" reality might lead to more serious issues around security, privacy, and reliability.

Maintenance and evolution present another challenge. Content creation typically involves discrete, finished products. Once you publish an essay or upload a video, it generally remains static unless you choose to edit it. The creator's ongoing responsibilities are minimal. Software exists in a fundamentally different relationship with time and change. Applications require updates, security patches, and compatibility adjustments. They exist within ecosystems that constantly change around them. When someone uses AI to create software without understanding its underlying structure, they may be creating maintenance obligations they're not equipped to handle.

This raises questions about the sustainability of democratized software creation. Will AI need to evolve not just to help people create applications, but to help them maintain, debug, and evolve those applications over time? Or will we see a proliferation of abandoned, potentially vulnerable software as creators move on to new projects without understanding their ongoing responsibilities?

All this creates new categories of technological risk and responsibility that we're only beginning to grapple with. It also suggests that the response to AI might need to be more sophisticated than our response to early internet technologies, precisely because the stakes and complexity are higher.

Individual creators aside, GenAI’s impact on software from vendors is another area of concern. Feature bloat is common in most software – armed with GenAI’s coding abilities, these vendors are likely to add more unnecessary features faster. Capitalism’s waste problem already exists in software – AI will worsen it.

5.

These days my feed – partly algorithm-driven, partly sought out with effort – surfaces articles and podcasts on AI and art, AI and the future of software development, AI and intellectual property, AI safety and existential risk, ethics and responsible AI, AI impact on labor, AI and human identity: the list of themes is long.

Such a collection of trending conversation topics, which really is the sphere of culture, suggests that the broad societal impact of AI isn’t somewhere in the future: it is already here.

AI has become a lens through which we interpret other phenomena and make decisions in other spheres of life, creating what we might call "cultural gravity"— AI discussions now pull other conversations toward themselves. Business leaders feel compelled to articulate AI strategies, educational institutions restructure curricula around AI literacy, artists define their work in relation to AI capabilities, and nations set up ambitious AI initiatives.

This cultural gravity didn't exert itself with the early internet in quite the same way. While the internet certainly achieved cultural prominence, it did so more gradually and with less existential urgency. People discussed the internet's implications, but they didn't feel the same pressure to immediately reorganize their professional identities or creative practices around internet capabilities.

Applications in the early internet era also developed relatively organically—people discovered uses for email, websites, and forums, then cultural understanding grew from these practical experiences. With GenAI, we're experiencing something different: cultural expectations about what AI should accomplish are driving development priorities before people have extensively experienced what it can practically — and safely — deliver.

This creates a peculiar situation where the technology must live up to discourse rather than discourse emerging from technological experience. When cultural expectations precede practical understanding, we may be more susceptible to both inflated promises and unexpected consequences.

While GenAI’s reach may mirror the internet’s, its trajectory seems different already. Using internet history as a guide can be briefly illuminating, but we’ll need new lenses to understand and keep up with this AI era.