Beyond the blinking cursor

Productisation of LLMs is an act of inclusion

Words and sentences are the material writers work with, but a blinking cursor on a blank page can be a source of anxiety for many of them. These days, using the technology people can’t stop talking about, we software folks seem to have no qualms subjecting everyone – not particularly those with a facility for words, but everyone – with a blinking cursor. The chat interface is our default choice for “AI-enabling” our applications. It is an infinite canvas, we think, and wonder why users stop after a basic prompt. The world’s knowledge is at their fingertips, we exclaim, so why don’t people use it more? The freedom to ask ChatGPT anything is indeed limitless, but it comes with a price. Kierkegaard, the Danish philosopher, identified it a century and half before our times: Anxiety, he said, is the dizziness of freedom. He was speaking about life, but AI nowadays seems to touch every part of it.

Or perhaps it is our belief that AI can touch every part of life. “Take X, and add AI to it” is the formula of our times. I found myself at the center of one such effort, giving a cohort of nonprofit users (enrolled into the ILSS Fundraising program) a session on ‘AI in Fundraising’. “Fundraising is all about connections,” I began, “and AI can’t be a substitute for the human connections you need to create and maintain in your fundraising journey; but it can assist you in your efforts.”

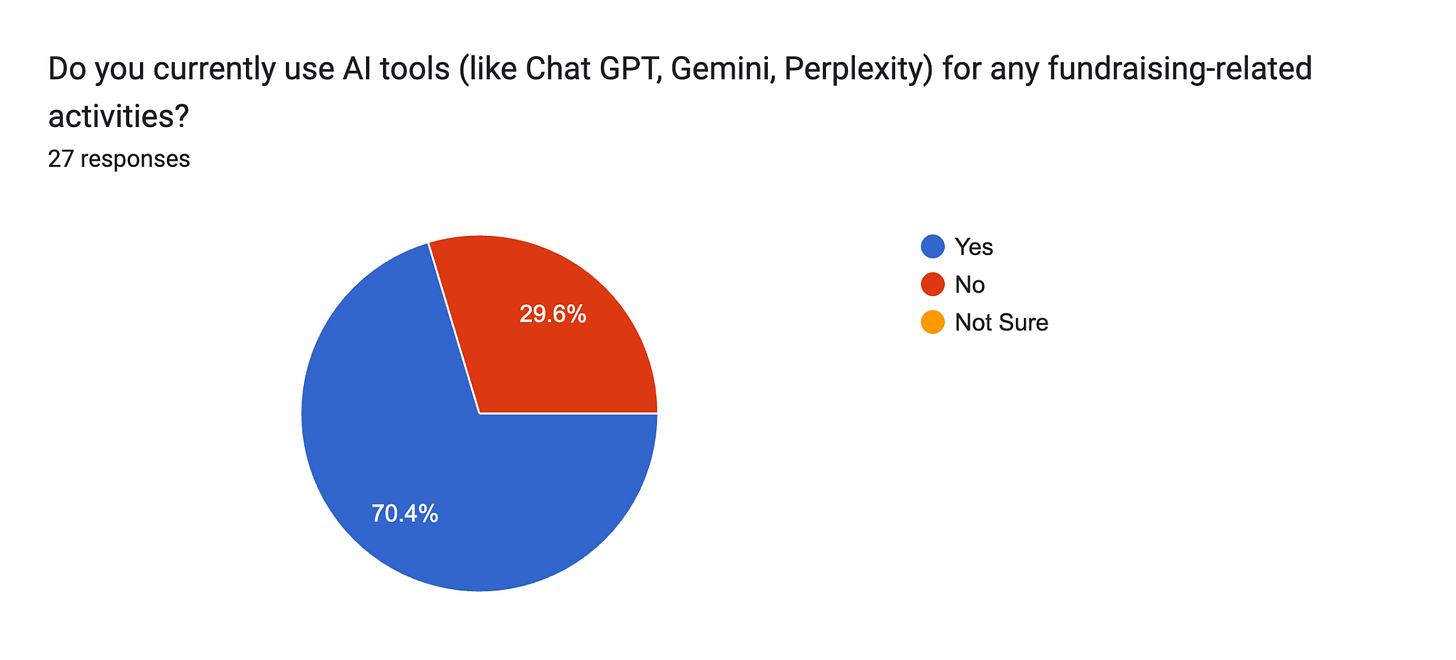

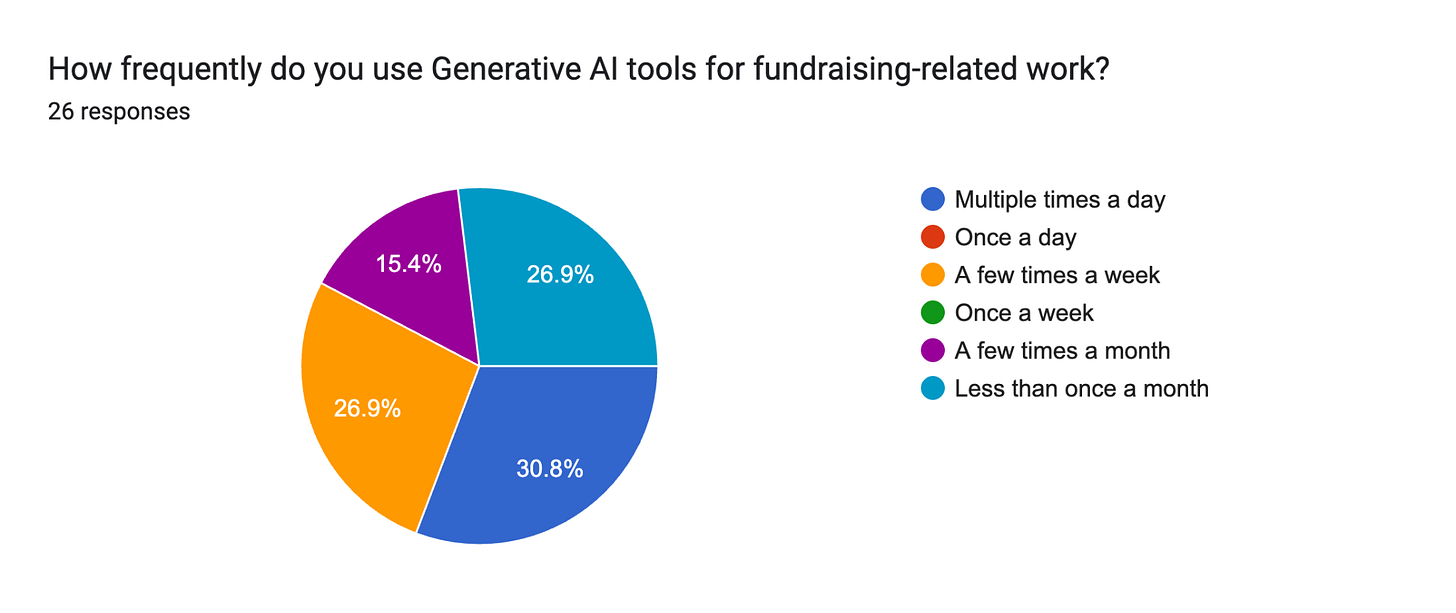

I’d designed the session as a workshop. Participants had to work on exercises using AI for research/analysis, ideation, building/generating, and review – all this along the fundraising lifecycle. This meant they all had to use the chat interface in a LLM-tool of their choice: ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, or Perplexity. A pre-session survey had revealed a wide variation in their AI usage patterns:

The exercises were straightforward – all files and prompts had been shared in advance – but not everyone seemed able to get through them. I noted at least one participant drop off somewhere along the way. She had struggled with the step of “adding a file” together with a prompt in the ChatGPT interface.

The intelligence and capability was all there, inside that box with the blinking cursor. One could use it identify the right donor, find ways to attract and convert them, build collaterals to keep them engaged, devise and implement strategies to retain them. But 30% of this cohort had never used AI in this context; of the remaining, only 30% used it on a daily basis; and now, in the workshop, extracting that intelligence, making use of all that capability, turned out far from straightforward.

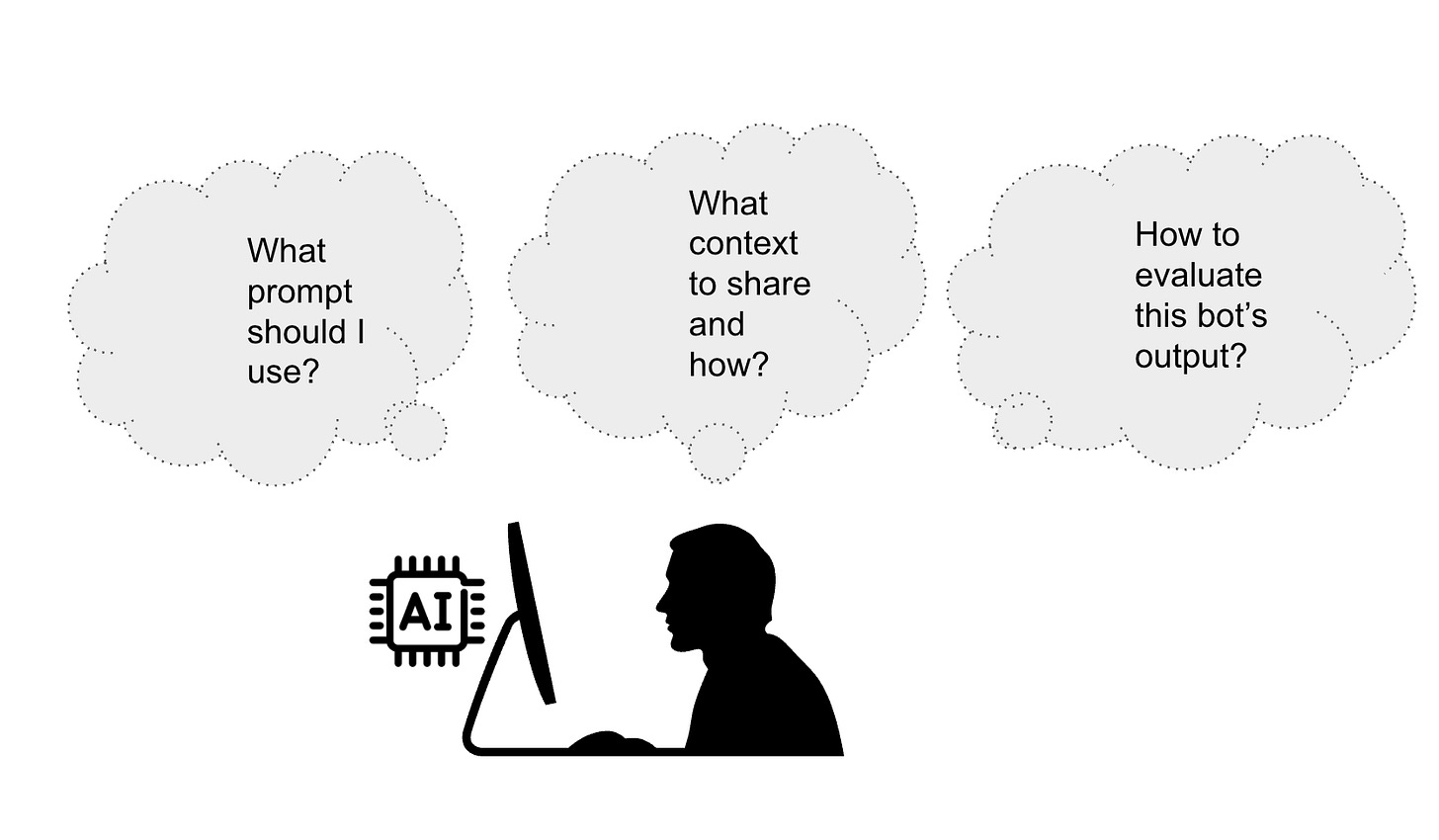

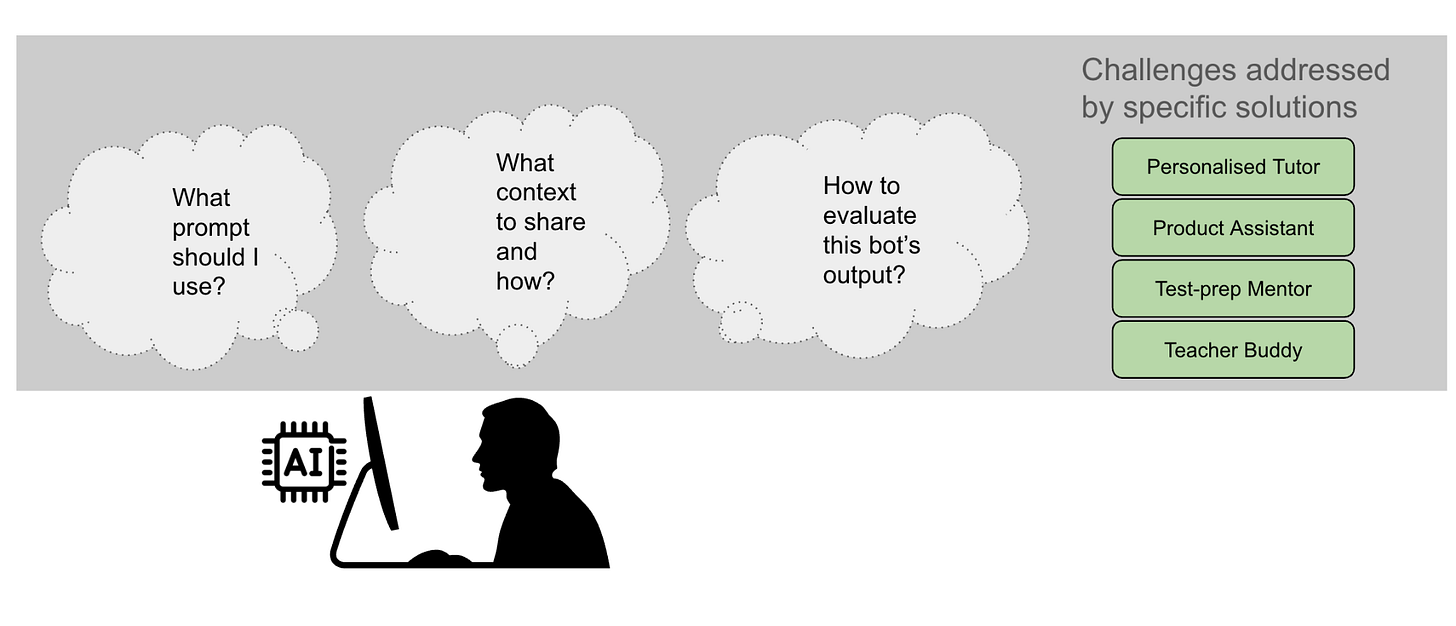

Aside from the matter of iterating over the prompt and choosing the right context based on their org-specific needs, there was also the issue of judging the output from these generic tools. With no expertise on the kinds of errors to look for, or experience with the way these tools can fail, judging such output is not trivial. Put another way, exposing such users directly to the output of ChatGPT-like tools places a lot of burden on them. And given the risk of incorrect output, it can lead them on a wrong path: an outcome worse than offering them no help.

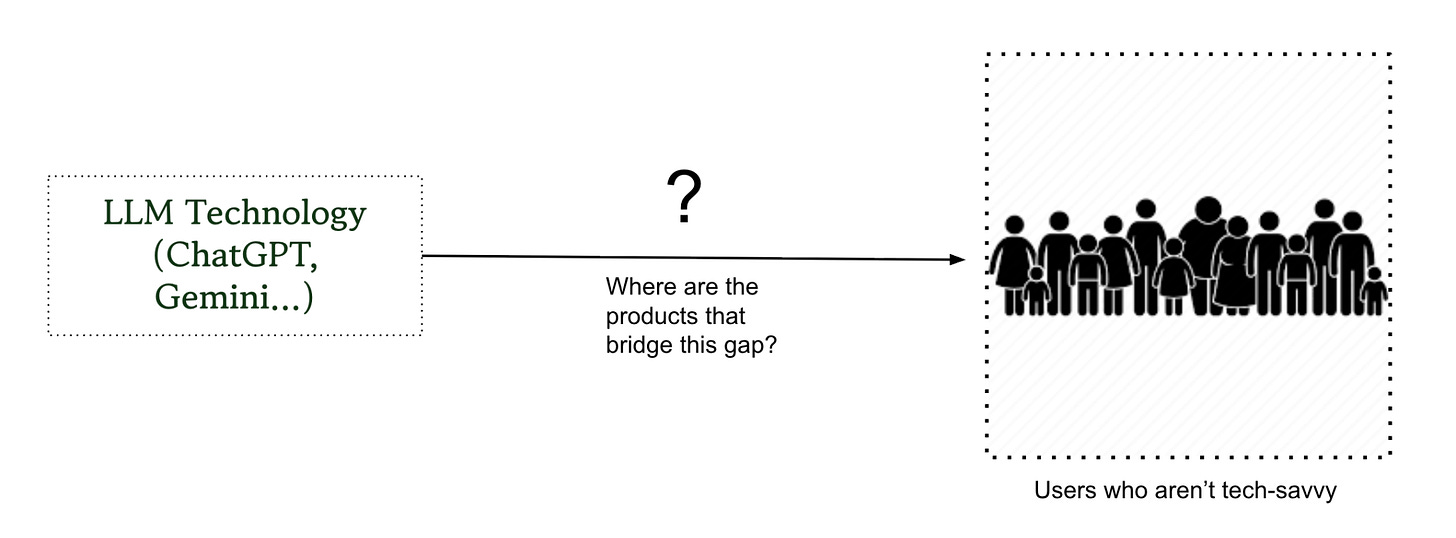

The missing piece was the glue between that “intelligence” and the “user”. The “products” that used LLMs to offer more than just a chat interface. Solutions that did not leave users staring at a blinking cursor, and later expect them to make sense of the generated output.

This became evident when I introduced NotebookLM at one point in the session. Only two participants had used this tool before. The others began to see its potential when NotebookLM was used to generate infographics, impact reports, short fundraising appeal videos, and to review a proposal targeting a specific donor. While not tailored to the fundraising use-case, NotebookLM demonstrated what a productised approach to using AI could look like. (Other products that do this specifically for fundraising – like DaanVeda, Agentforce, Wealth-X, etc – were mentioned, but given the diversity of the audience we had to use commonly available and free tools for the exercises.)

Building products around LLMs seems like a no-brainer, but linked to it are a host of challenges.

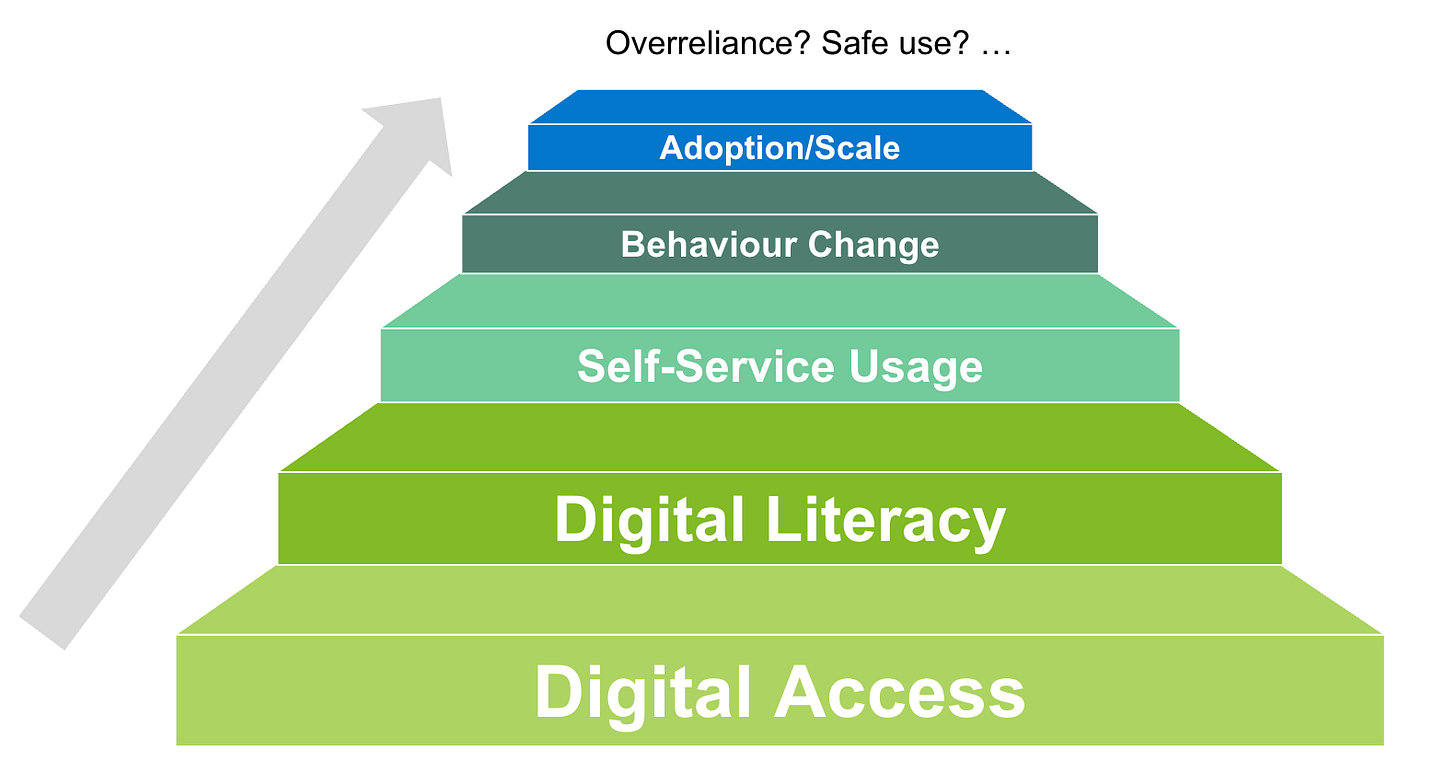

Here were users – from communities in the social sector – who were not as digitally literate as many of us propagating AI (or tech) usage. For some, even access was a problem.

Beyond digital access and literacy, there was the challenge of self-service usage: users from this sector often struggle to navigate user interfaces by themselves. Handholding them is often needed.

If you solve these, if you acquired digitally literate users comfortable with self-service usage of your software, you hit the challenge of behaviour change: how to get users to proactively use your new approach – a new process or practice using your software – overcoming years of alternate practices and habits?

Solve that and you get broad adoption, but then run the risk of over-reliance on AI (or the automated solution).

And cutting through all this are questions and risks around AI safety.

Who was working to address all this?

* * *

A week before this ‘AI for Fundraising’ session, I attended the closing workshop of an “AI Cohort” program from Project Tech4Dev. This was a group of seven Indian nonprofits working on AI-enabled solutions to solve specific problems within their programs. (I’d written earlier about the first workshop with this cohort.)

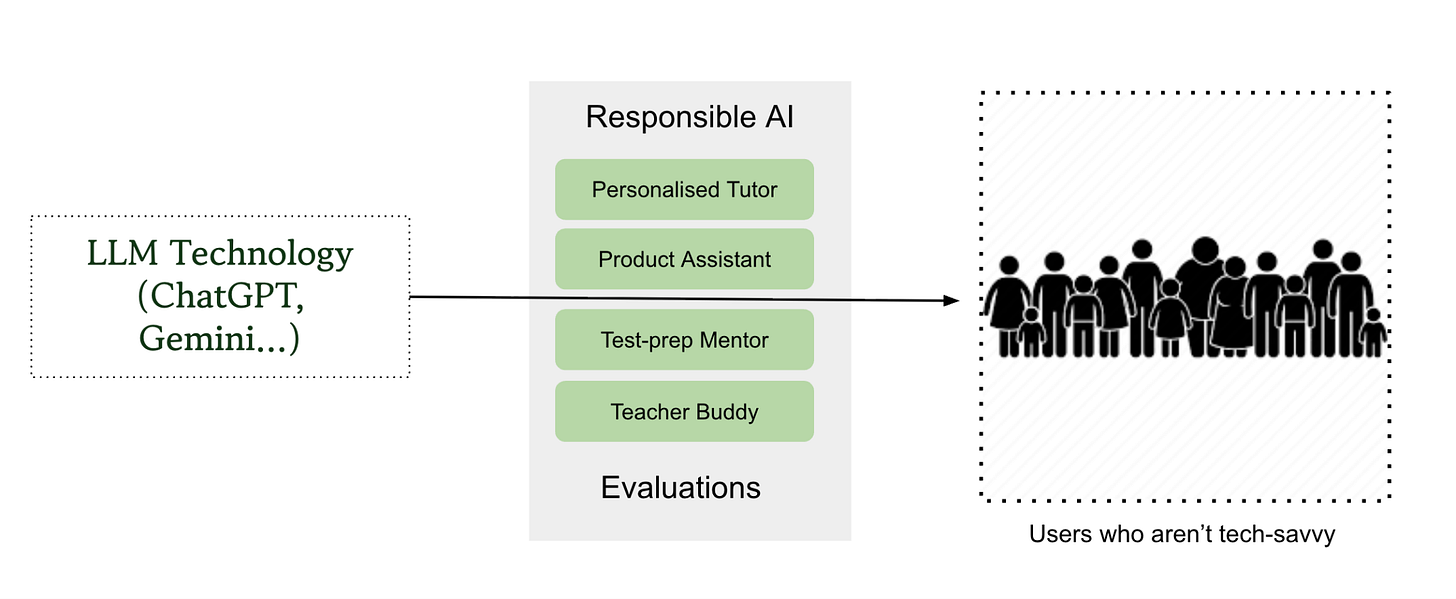

Five of them were building LLM-based products. And in their own way, these nonprofits (along with a couple of knowledge partners) were tackling the aforementioned challenges around AI/tech adoption within this sector. (For a detailed roundup of this December workshop, read this post from Project Tech4Dev).

Quest Alliance was taking a novel approach towards a personalised tutor. Using a “behaviour classifier” to identify micro and macro user behaviours, and combining it with the complexity of the user-query, the tutor surfaced responses in tune with user’s learning ability. The aim was the address the gap – “the missing middle” as they called it – between the user and generic AI tools (like ChatGPT) that do not capture or retain such user context. So here was one entity trying to solve the “literacy” challenge by tailoring responses based on identified literacy levels, and also targeting “behaviour change” through learning-level based nudges.

Avni, a data collection and visualisation platform, was addressing the complexity of “self-service usage” by introducing an LLM-based assistant that answered questions, explained features, and configured the application. This was an inversion of the chat interface approach: complementing UI-based interactions through a chat-based assistant tailored to a specific set of tasks.

Avanti Fellows were using LLMs to help teachers offer personalised test-prep guidance based on student test scores. In contrast to a vanilla chatbot-based approach, this solution offered a structured response generated by AI through a pipeline of prompts and guidelines that made the suggestions set to the right tone, grounded correctly on data, and with clear rationale for suggested steps. In other words, recommendations that enabled teachers to consume and implement them without fussing over their quality.

Simple Education Foundation was building an “AI-powered teacher buddy on WhatsApp” for government school teachers. The “AI” part of the solution was limited to the end of the user-journey, after context was retrieved through menu-driven questions. The bot responded to simple user queries with concise summary of the classroom strategy to be used, along with a link to government-approved material – a video, or a PDF – that had been used in the initial teacher training.

These solutions were attempts to fill that gap between “intelligence” and the “user”. Here, the skills users needed in prompting, providing context, and evaluating output were either eliminated or significantly reduced. And this productisation was an act of inclusion: by hiding the prompt/context/evaluation specifics, these solutions were ensuring equitable access to AI for people who would otherwise be left behind.

There was more to this “AI Cohort” program. Supporting these nonprofits were two knowledge partners, Digital Futures Lab and Tattle, who brought their expertise on Responsible AI and AI safety, and shared with the teams specific principles and guardrails. There was also an open source technology developed Tech4Dev that enabled “Evaluations” of the output generated by these solutions.

This approach, an early attempt in this sector to close that gap between LLMs and the users, hints at how the Gen AI space will evolve. We are going to see more specialised and local solutions, often substituting the powerful but generic chatbots. As Sebastien Krier from Google Deepmind says:

“Local knowledge can’t be centralized…The knowledge required to deploy AI usefully - what workflows need automation, what error rates are tolerable, how to integrate with existing systems, what users will adopt - is dispersed across millions of firms and contexts. It’s often tacit and contextual rather than explicit and generalizable. A model can’t just internalize this by training on more data, because much of it is generated in the moment through interaction with specific environments. Even arbitrarily capable models would still require an adaptation layer to translate general capability into specific value.“

That “specific value” is what the nonprofits in this AI cohort program were creating. And these solutions were being designed by people who understood the local context well.

* * *

The two cohorts I interacted with could not have been more different. One was full of engineers and product experts fluent with technology; the other had people from diverse social sector backgrounds, with limited tech understanding. This exposure, starkly juxtaposed in the space of one week, made clear the importance of bridging the gaps surrounding AI: the gap between intelligence and users’ ability to leverage that intelligence, the gap between software capabilities and the users’ ability to consume them, and the gap between the speed of AI evolution and its safe usage.

We need more such “AI cohorts” to work on these gaps. Using AI to close gaps between AI and the user isn’t quite the contradiction it initially sounds like. That’s the beauty of this general purpose technology we are grappling with. While some of us stare at a blinking cursor, others are plotting ways to move beyond it.

Looks like a platforms vs applications discussion again 😉 As always devil is in the details and in execution. Your team seems to be working on both 😀